As recently as the 1980s, the farthest an academic could make it in the world of popular culture would have been a brief appearance on the Today show to flog a new book. But cultural studies has changed all that. Now that professors have been churning out books and articles about rap, Elvis, and Madonna, the bemused performers are beginning to scratch the occasional academic back, or better, blurb the occasional academic book. Consider, for example, the quotes on the back cover of Michael Eric Dyson’s recent Making Malcolm, from Oxford University Press. In addition to the more predictable endorsements from Cornel West, Angela Davis, Jesse Jackson, and Carol Moseley-Braun, we also hear from Chuck D of Public Enemy: “With the situation getting more hectic, the real troopers come far and few. And with misinformation spreading, it is a necessity to follow Michael Eric Dyson. He’s a bad brother. Check out his new book Making Malcolm by all means.”

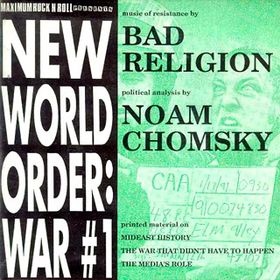

The rappers’ reverence for cultural studies scholars hardly comes as a big surprise; Dyson, after all, testified on behalf of rap music at a congressional hearing in 1994. More startling, however, was the recent report that MIT linguistics professor Noam Chomsky is a major fave with top rock musicians. Rock & Rap Confidential magazine describes Chomsky—the embodiment, we had always thought, of old-fashioned leftist rectitude—as “a quote machine with all the rockers.” Chomsky’s anarchism has also made him a hero to punkers: Bad Religion put an entire Chomsky lecture on the B-side of one of their seven inch singles. And Maximum Rock’n’Roll, a leading fanzine with a circulation of 10,000, reprints Chomsky’s speeches for its Generation X readership. Other tributes abound: In 1994 an Austin-based band called The Horsies did a single they titled “Noam Chomsky.” U2’s Bono has called Chomsky a “rebel without a pause” and “the Elvis of academia.” And Peter Garrett, shaven-headed lead singer for the Australian rockers Midnight Oil, launched into a song called “My Country” at a Boston-area concert by invoking the following trinity: “Thoreau, Noam Chomsky, and…the Hulk!”

The Chomsky connection appears all the more remarkable when one learns more about the linguist’s own rather unusual relationship to mass culture. Because Chomsky can speed-read any document, he apparently grows impatient with the slowness of the fast-forward mode on a VCR. A friend who sought out a Chomsky blurb for a radical video was told by a go-between that the professor might consider wiring an endorsement after he read the script, but he refuses to screen films. He even declined to watch Manufacturing Consent, the documentary about him, and instead insisted the producers give him a transcript. (Unfortunately, he’ll never see Pulp Diction, Quentin Tarantino’s soon-to-be-released homage to Chomsky’s 1965 best-seller, Aspects of the Theory of Syntax.)

All of this raises the intriguing question of whether Chomsky has vetted the rock encomiums to his work. If he has, we would guess that this means that there are now two people who actually read rock lyrics: Noam Chomsky and Tipper Gore.

= = =

Lingua Franca: The Review of Academic Life, May/June 1996, page 10.