In 1986, industrial musician Boyd Rice appeared on Tom Metzger‘s talk show Race and Reason. Metzger, leader of the White Aryan Resistance, was one of most important—and violent—leaders of the White Supremacist movement in the 1980s and ’90s. After this video resurfaced in the late ’00s, it has been consistently forced off sites like YouTube, and so we have made a transcript. To date, Rice has never addressed this video.

[beginning title card]

Race and Reason

Date: 12/30/86

Series #42

‘copyright’ Alexander Foxe 1986

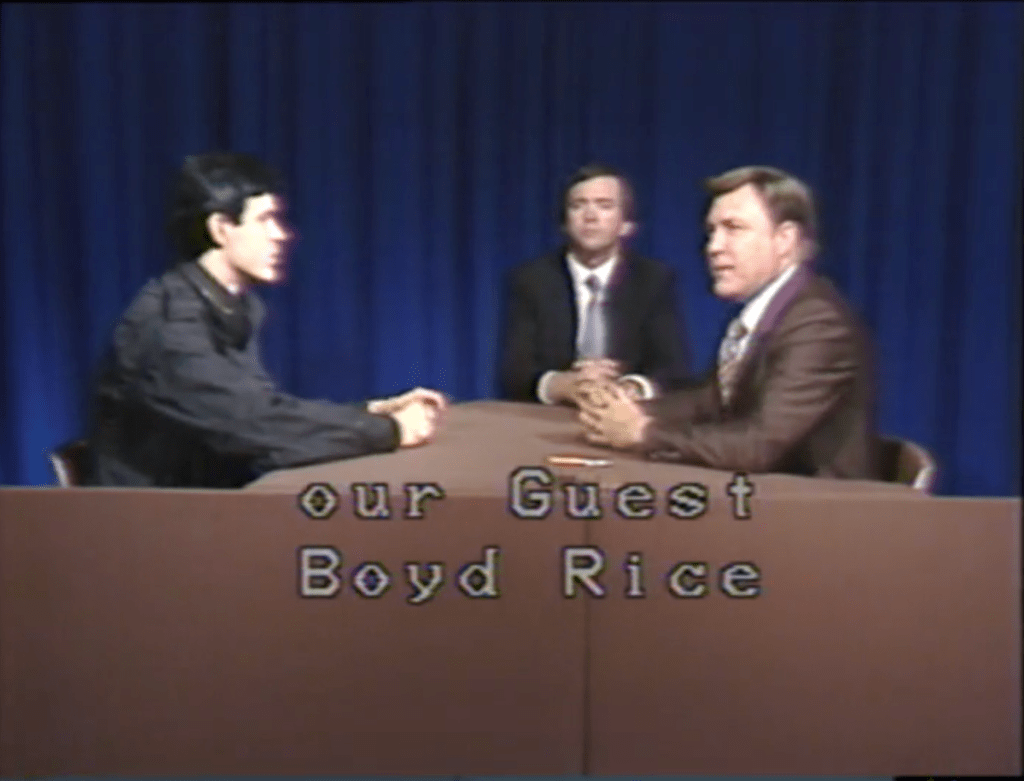

Host

Tom Metzger

Co host

Tom Padgett

our Guest

Boyd Rice

Metzger

Hi, I’m Tom Metzger, your host for Race and Reason. Race and Reason—dedicated to real free speech, that small island of free speech in a sea of controlled and managed news. And we’ve got a show for you—about what, Tom?

Padgett

Well, let me, let me introduce Mr. Boyd Rice on my right, who is somewhat of a cult figure in the racial underground musical world. And Mr. Rice has also in quite a few other different things, which we’ll be trying to cover in the next half hour. Mr. Rice, welcome to the show.

Rice

Nice to be here.

Metzger

Nice to have you with us. What is this underground racial music? See, I’m forty-eight, maybe I’m not supposed to know about this. What’s happening, Boyd?

Rice

Well, first I started out being just a member of the music underground. I did avant-garde music for years and years, then traveled around and gave concerts and met people all over who were doing, you know… [had] come to a similar place as me, who were doing similar things about, you know, we didn’t know each other. And we just sort of arrived at the same place somehow.

Padgett

Tom says he saw your act here in LA or someplace.

Padgett

This was about six, six years, six-and-a-half years ago.

Rice

Yeah. Well…

Metzger

Now I get the impression—or you said something about—you use soundtracks and various things. It sounds like very different than what we’re used to.

Rice

Yeah, yeah. I think most people who make music are making music for, for the, for the mind, if you understand what I mean. I’m making music more for the brain. It’s like the mind is sort of human, humanized, and sort of has to do with society and the culture out there. But the culture that really doesn’t have anything to do with what, what I am or what you are.

Metzger

Is it more for like, just an emotional need? Or is it…

Rice

It’s, I think it’s something you listen to it, and it gets your mind to start thinking in a different way. Because it causes you to experience things that ordinarily I don’t think you’d experience.

Metzger

This is not necessarily connected to like drug cults or anything like that, right?

Rice

Drug cults? No. You’re talking about like trance music?

Metzger

In other words, you’re trying to get people on their own natural high.

Rice

Yeah, yeah, basically.

Metzger

Would you say that type of music is uplifting?

Rice

I find it very much so but, but for some people, people who are resistant to it, they find it you know, painful and horrible and they think I’m just trying to torture them with sound.

Metzger

Now I understand you’re quite well known in Europe and in England, maybe better than here. There’s a lot of Americans seem to end up with that type of a hand. I hear you’ve cut records for…

Rice

yeah, for years.

Metzger

and you own, had record company and…

Rice

I don’t own it. I’m signed to a record company in England. It’s like this major independent label called Mute.

Metgzer

So you’re probably even more well-known over there than you are here.

Rice

Yeah.

Padgett

Well, don’t you feel Europeans are more receptive to different types of music. Seems like a lot of Americans are in a rut with Top 40 or the same rock and roll that they heard ten years ago. It’s like they just can’t seem to break out of that and listen to anything new. Europe, Europeans do seem… the time I spent in Europe, they seem far more receptive than Americans do.

Metzger

Well, what’s the evolution of this underground music into the more, say, white racially oriented music? How did this evolve? You probably would be someone who could really clear that up.

Rice

Well, I think it came as sort of chaos of like… I was basically I was on the fringes of the punk rock scene, though I never considered myself part of it. And that sort of came about just naturally as all these people were dissatisfied with what was going on and they, they realized all the values they bought into are just garbage and didn’t have any sort of any function in their life, and they just wanted to throw all that off. And in the process of throwing it off, you know, most of them just just thought of a freedom sort of unfettered individualism, and then they’d get to a certain point, and they’d realize they’re going through all these motions, but they really weren’t being any more free. And so from that point of like throwing off all the values, I think that you have to come back to something, something organic.

Metzger

Some type of discipline?

Rice

Yeah, some type of discipline or, you know, you get back to this biological knowledge of what you are and what nature is and where your place is, and so forth.

Metzger

You know a lot of these racialist-type singers and bands and Europe and Britain. Could you mention a few that… I know that you, you know the skinheads, and you’ve mentioned some others.

Rice

Yeah, there’s some there’s a guy I know named David Tibet who has a band called Current 93, who’s moving more and more towards racialist stuff. And he’s friends with some people called Death in June, who’re very racialist oriented. And we were… they’re actually, they’re… Death in June is quite popular now. And there’s another electronic band called Above the Ruins. Which, there’s a guy in it who is in Skrewdriver—that’s a British skinhead band.

Metzger

Now is that group more like National Socialist oriented? Or fascists, or what?

Rice

Which group?

Metzger

Well, the last group above.

Rice

Death in June? Oh, Above the Ruins?

Metzger

Above the Ruins.

Rice

I haven’t really heard About the Ruins yet, I’ve just heard of them. But I know, it’s, there’s one guy from Death in June and one guy from Skrewdriver, so I assume it’s…

Padgett

Well, I’d have to interject that electronic music is very white, just by it’s, by it’s very nature. You don’t see too many non-whites listening to that kind of stuff. It just seems intrinsically white to me.

Metzger

Well, our producer here has been into electronic music for a long time, Dave, Dave Wiley. And I don’t think it plays on the same wavelength as a lot of the minorities. That’s my opinion, but I’m surely not a, an expert on this.

Rice

Yeah, yeah, that’s what I feel, too. In fact, people in the press this, this music I do, the press dubbed it “industrial music” after this one band that called themselves, you know, said that what they were doing was industrial music. And it had been said that this was the first white music, you know, come out and hundreds and hundreds of years. Because a lot of the popular music has been influenced, you know, black influence—Little Richard and so on.

Padgett

Exactly. Well, this is something that’s downplayed. The media likes to characterize us all as being one people and one mass, but seems like a lot of rock concerts are the most segregated thing since a Klan rally?

Metzger

I would I would think so. Now, I haven’t been to many, but I’m waiting to be invited. /laughs/

Rice

Well I haven’t been to any rock concert in years, you know?

Metzger

Yeah. Well, rock concerts, though. From what I can gather so many of are so full of drugs and stuff, and it’s gets pretty bad. But I, but there seems to be a difference between that and what the skinheads are promoting and people like that, or at least the racially conscious.

Padgett

The point is, we all don’t like the same music. All races don’t like the same music, at least from what I can see.

Metzger

Another question I’d have with like, in Britain, can you say things in music that you go to jail for if you print or say in a speech? Is this a way around…

Rice

I think you can say it in music in a different way, because music, music can speak to the soul, and you can say things through it, that you wouldn’t be able to just come out and say. Or if you said it to somebody, they could understand it intellectually, but they wouldn’t really know it. I mean, you have to sort of experience something to really know it.

Metzger

So whereas modern music has been pretty much propaganda instrument of Jewish interests and, and black, soul and so forth, you see emerging a new propaganda art form for for white Aryans.

Rice

Yeah, yeah, I think so.

Metzger

Now, it seems that a lot of the music I’ve heard like from the skinheads, was this really repressed, suppressed anger at what the system is doing to the youth of Britain.

Rice

Uh huh.

Metzger

That comes right through and like I’ve asked before, why has that not broken through yet? I mean, I… 25% unemployment and this rage that’s building—why hasn’t it spilled over really into the streets? What keeps England from blowing sky high?

Rice

I think just, just little handouts everybody gets from mommy over there. You know, it’s the whole country is this matriarchal place where they have this, Margaret Thatcher, and they have the queen and it’s like, it’s like their mommy giving them money.

Metzger

The dole.

Rice

The dole. Yeah.

Metzger

That seemed to be what I got from our English friends who came over here. And they seem to be still hung up a lot on the Queen and things like that.

Rice

It’s ridiculous, you wouldn’t even believe it. Like over there you can even be put in jail if you put a stamp on upside down, because the stamps will have the picture of the Queen and that’s like, blasphemy or something like that. There’s actually some charge against it. You can be jailed for that.

Padgett

So when the Sex Pistols came out with that song, “God Save the Queen, She ain’t no human being,” I guess that was quite a shock to the British people then.

Rice

Yeah.

Metzger

I noticed also that there’s such a super strong streak of ultra-nationalism in Britain. Yet that, uh, there are so many of the youth are really prepared to march out and do another, like the Falklands or something. These idiotic military ventures that just get Aryan people killed, when their big problems right there in Britain—the same way our problem is right here in United States, not in Central America. It is, you know, strange…

Rice

It’s like, you know, yeah..

Metzger

…it’s strange. It’s hard to figure that the reasoning and the rationale doesn’t sound correct to me. I mean, if you’re 25% of the young people out of work, you gotta blame somebody besides the Argentines? I mean, you got to start putting it, putting it where it’s at, and the fat cats in the corporates in Britain, don’t you?

Rice

Yeah, but that’s, that’s why I have those little things to draw people’s attention over, you know, it’s like, like the Manson trial or something—where everybody’s like, pissed off this one guy, “He went and murdered six people!” And you know, it’s to draw their attention away from the Vietnam War, and all their brothers and sisters that are over there getting killed every day. It’s like they had it like the football scores up on TV.

Metzger

In other words, if you have a license to kill, it’s okay.

Rice

Yeah…

Metzger

If you’re in the government, you have a license to kill millions. But if you’re not licensed…

Rice

if you’re not licensed, then they focus all the attention on this one person, you know, so you don’t…

Metzger

Yes. Now, you mentioned earlier…

Rice

…get your attention off where it should be…

Metzger

…that you tended to be, in a broad sense, pagan and Odinist and like that. Would you explain that a little bit to our audience?

Rice

hmmmm..

Metzger

Just from your own point of view.

Rice

/softly/ from my point of view,

Meztger

Well, not from mine! /laughs/

Rice

OK, well, let’s see…

Metzger

Well, like the Odinists, see we’ve had Odinists on, and Tom’s been with the Odinists for a long time, sort of a Viking-type religion and…

Rice

Yeah, I think it’s a more natural type. It’s not, not so much a religion—well, it is a religion, it’s a spiritual thing. But it’s, it’s something that I think is organic and comes from within…

Padgett

Almost like all music, it springs from the soul, it’s natural and native to us.

Rice

Yeah.

Padgett

And music’s a part of culture, so is religion.

Metzger

Well, isn’t this evolving in this music? What’s it called, neo-pagan type—in a good sense, not being run by a priest craft and so forth?

Rice

Yeah, exactly. I think it’s something that the more relates to, biologically, to what what we are, what I am. And those are the things that satisfy me the most, the things that come from within, you know. I’m always looking for… for a lot of people, I think a lot, a lot of people are looking for answers outside of themselves. And I think all the answers are within yourself.

Metzger

Well, what are you going to do to get the ball rolling more in this country? We’ve had skinheads on the show, and they’re sure out there doing their share, and seem like they fit in with just about any white racialist group that had much sense. What’s going to get this moving, what’s going to get this type of music—that appears to, you know, be attractive to white youth—moving in this country? You know, the major, the major record companies are not going to beat a path to your door, right?

Rice

Yeah, that’s for sure.

Padgett

That’s, I think, the understatement of the show.

Rice

But I think this music appeals to certain core of people. Like, there are people everywhere, who are, sort of, feel not a part of everything else that’s going on around them. And people like them don’t have any music. And this is like music for them. I’m sort of like doing something for myself. I… that’s what what started me into music. I was just completely disenchanted with everything there was to listen to, because it was just, you know, it’s just stuff that programmed people to be weak and cowardly. There’s no good, there’s no values you can look up to in any of the music that’s on the radio today. There’s no, you know, positive role. You know, male role models in the rock music today…

Padgett

I think a lot of people don’t even consciously listen to the music that’s on the Top 40—it’s just something that’s on, and it’s just noise and, and whatever.

Rice

Yeah, that’s the worst part. Because if you don’t consciously listen to it, it just flows right into your subconscious mind. You just, you know, affects all your behavior and it really dictates…

Padgett

Very, very subtle, wouldn’t you agree…very, very subliminal, very subtle, very…

Rice

Yeah, yeah, completely subliminal. But I think even the people who are making this music aren’t even conscious of it. Because they’ve grown up with these, with these pitiful liberal humanist values. And then, you know, comes time for them to do what they think is expressing themselves, and they just reiterate the same stuff that’s been fed into them.

Metzger

Isn’t it interesting when you listen to people being interviewed around the country how they all begin to use the same words? And I can’t think of them all right now because I try to forget them. It’s, it’s like, listen[ing] to the same person, whether you’re in Illinois or California.

Rice

It’s like whenever you read Mein Kampf referred to in print, they always use the exact—there’s like several words they always refer to. They call it turgid, turgid prose and incoherent, and stuff. And it’s like, the exact same words wherever you see it mentioned in print. And it’s like, they all got it from the same source… was like, just meant to discourage people from ever reading that because when you read it, you know, it’s the exact opposite.

Padgett

But wouldn’t you agree Boyd that most people don’t think for themselves?

Rice

Oh, I definitely agree. Well, I mean, think…you talk about think, but when you think with the human mind, you’re thinking in the terms that have been put into it. You know, you’re thinking in those terms, and you use those words, those words are—reflect the value system of—you know, the world out there, not the world within. So it’s even if you think you’re thinking for yourself, you’re still thinking in the same terms that everybody else thinks in. So you’re, you know, you’re still a step removed from yourself, if you know what I mean.

Metzger

Staying with like the subject, [inaudible] Mein Kampf: How can the people, and people all over the world, listen to this explanation that Hitler said in Mein Kampf, that he was pushing “the big lie.” And that’s what’s told millions of people and they repeat it every day. When all they have to do is open up Mein Kampf, and if you’re going to be intellectually honest—no matter who the person was, they should read—and that’s not what he said at all. And he said ‘here it was the Jewish people who are controlling things, that were using the big lie.’ Now anybody in America can go down to a library and get Mein Kampf. And look in there and see, did Hitler say that, or didn’t he say that? But yet, they’re so…

Padgett

They don’t read!

Metzger

So blinded…

Padgett

It’s, it’s, it’s the television.

Rice

Yeah…

Metzger

They’re not intellectually honest. I mean, they seem to wallow in “it’s good to be stupid.” Now, do you feel that the music that we’re talking about here is sort of the beginning of an orchestration of an Aryan underclass movement?

Rice

I think so, I think it’s engendering a new will, among people. That’s, that’s what, what I’m interested in. And bringing about the, you know, self-reliance and inner strength and the qualities that are naturally part of you. I mean, I think, you know, we are naturally weak and cowardly. We just, we’ve been taught that, we’ve been taught to be afraid of things and, and to let other people do our thinking for us.

Metzger

Do you think that your music, like your own music, is such that people of various ages could sit down and, and tune in—you don’t have to be a teenager to get into it?

Rice

Some of it, some of it, it’s very appealing to a whole wide spectrum of people. Some of it, some of it is less appealing.

Metzger

Well, I found that a lot of these groups that are putting out music, the lyrics, I think are great, but I can’t understand what they’re saying when I listen. You know, it’s so loud and the instruments are so loud. I can’t hear…

Padgett

You’re over thirty now.

Metzger

Yeah, I guess so. And I’m trying, “What’s he saying? What’s he saying?” Then I read the lyrics and I say, “Hey, that’s great!” [turns to Padgett] Come on, Tom, don’t tell me you understand everything they say!

Rice

But it’s interesting. One, a reviewer, who knew absolutely nothing of my tastes—or my likes, or dislikes, or anything—compared my, compared a certain record I did to “Ring Cycle” by Wagner. I mean, it’s, there’s…it bears no resemblance, really. And yet there was something in there that that person related to. And would choose in his mind to compare it to that, without knowing anything about me.

Padgett

Possibly just subconscious racial memory or something.

Rice

Yeah.

Metzger

Well, then. Do the young people understand all the lyrics? Or aren’t some of them just sort of go through the motions?

Rice

Well, I’m not sure …

Metzger

I’m not talking specifically about your music, but you know, some like the Skrewdrivers.

Rice

Oh, yeah, Skrewdriver, people definitely understand what they’re on about, because they make no bones about it. They’re very upfront about it.

Padgett

I guess the younger people listen faster.

Metzger

But have you been over to Britain at all or…

Rice

Yeah, many times. I’ve toured over there and played there, and I’ve been over there in recording studios.

Padgett

Did you tour anywhere else in Europe?

Rice

All over Europe. Berlin, Paris, all over.

Metzger

Have you had any trouble with the authorities?

Rice

No, uh uh, they’ve been, you know…. what I’m doing is pretty obscure. It’s pretty hard to look at it, you know. But yeah, I’ve had, I’ve had problems coming into the country to play concerts a few times, but that was just related to work permit problems and stuff.

Metzger

Could you, would it be any radio station you think in this country that would, like, put one of your tracks on once in a while?

Rice

Yeah, a lot, a lot do it all the time.

Metzger

Good.

Rice

But you know, like, kind of underground stations and college stations, you know, not in the Top 40.

Metzger

Well, we’re gonna worry about you if you ever get to the Top 40.

Rice

Don’t worry about me.

Metzger

And, so, is there a language barrier when you get over to these other countries, or?

Rice

No, everybody speaks English, all Europeans speak English.

Metzger

And mostly it’s, what, teenagers and in their twenties?

Rice

Yeah, yeah.

Metzger

Well, do they draw pretty big crowds over there?

Rice

/nods head/

Metzger

Pretty big.

Rice

So I’ve played for, like, 3,000 people.

Metzger

3,000 people?!

Rice

Yeah.

Metzger

Geez.

Rice

The Lyceum in London.

Metzger

That’s really something. That’s, uh, I don’t think…. [to Padgett] Do you think Little Richard could get that many? Probably not anymore—he went back to being a preacher, I understand.

Padgett

Well, that’s quite aways from a small club in Hollywood where I first watched you perform, so…

Rice

I’ve played for audiences… I play for five people and you know, 3,000. And everything in between.

Metzger

Well, one, one, we got to find a place where we’d come and listen to you or something and hear the music. I’m really intrigued about this.

Padgett

You haven’t heard this guy?

Metzger

Well now, explain a little bit what you do on this stage. I mean, you were explaining a little bit before the show—you have soundtracks…

Rice

Yeah, I try and use sounds that are unclichéd sounds. Like most musical instruments, you’ve heard them a million times, and you know how to react to them, and you know what they are. And, and even electronic music, you just kind of the, the frequencies sound a bit foreign to you. And I try and use things that are more sounds that you have to experience. And when you feel them, you don’t really know how to react to them.

Metzger

But that’d be like natural sounds and the outdoors?

Rice

I use a lot of noises. But then I use natural sounds as well.

Metzger

You know, he’d been describing this to me for some time, but I just can’t quite zero in, I…

Padgett

Well, it’s tough to explain. I’ve seen, I’ve been to one of his performances live and it’s hard to put into words. It’s almost like, you’d have to, you’d have to be there. You know?

Rice

Yeah. It’s meant to be as an experience…

Padgett

And that it is!

Rice

You experience it, rather than listen to it, sort of force all this stuff out of your brain.

Metzger

Have you played some known places in the United States—clubs that people would, some people would be familiar with?

Rice

Played the Whisky-A-Go-Go in Hollywood.

Metzger

Oh, I know about that.

Rice

Have you ever been to Kelbo’s in Hollywood, or Chico?

Metzger

No, no.

Rice

It’s great, it’s a Hawaiian barbecue.

Metzger

Oh, I know where that’s at! Oh, I have too been there, sure. You played there?

Rice

Yeah.

Metzger

See, I wish I’d have known about that.

Rice

I might play someplace in Los Angeles soon.

Metzger

Well, next time you do, I’d like to know. Do you plan to go back to Europe?

Rice

Yeah, yeah, they just want me to go back there just recently, but they didn’t give me enough forewarning, so…

Metzger

So you have friends in the National Front in Britain?

Rice

Um, I have friends who are interested in that, and affiliated with those kinds of people, but I’m not sure if any of my friends are actually in the National Front.

Metzger

What do you think politically is happening? I mean, you know, you’re into the music, but you’re obviously, to a degree, a music propagandist in the, in the broadest sense. What’s going on in the political, and…what’s cookin’? What’s coming up?

Rice

Here or in England?

Metzger

Well, here.

Rice

Well here, I’m not sure…

Metzger

Which way are we moving in this country? Are we moving towards a police state?

Rice

I don’t… is it moving towards a police state? /laughs/

Metzger

Yeah, you already think it’s here!

Rice

I’ve always kind of felt like politics was for people who couldn’t run their own lives. I’m always, you know, I think things are, things are getting bad, obviously. But, but I’m more interested in a sort of a rebirth coming from—like, there’s a line of Greek tragedy that says, “Where the root lives, yet, the leaves will come again.”

Metzger

Probably, in other words, from the inside out, from the bottom up, and don’t worry so much what’s going on at the top, just change things. What is it, does it have any…

Rice

This is, this is what’s happening with me. And this what’s happening with people I know. And it’s sort of hard to translate something like that into, into politics, because a lot of politics is just contrite and just structures that really have nothing to do with…

Metzger

Well, when I say politics, I use it generically, in the broadest sense of what’s going on in the country and our institutions and in the government and its relationship to the people. Would you see yourself more as an anti-system, anti-state individual, as opposed to be a state worshiper so to speak?

Rice

Yeah, I see myself as anti-system and anti-state as long as the system and state are completely contrary to, to what people are, and to what people should be.

Metzger

The state…

Rice

Should allow them to be what they are.

Metzger

Well, the state in a super-state seemed to take on the Divine Right of Kings idea, of the Divine Right of the State. Have we outgrown the state?

Rice

Yeah, the state as it currently exists. We certainly have, I’m sure.

Metzger

Especially like a super-state? You know, the United States and Russia? Have these super-states become so big and unwieldly that they just, they do not represent anything that’s intelligent?

Rice

I think so.

Metzger

Well, how do you feel about racial separation and tribalism, and, and…as opposed to national borders and things along these lines?

Rice

Like seems like, it seems like the only intelligent way to go. It seems like the way people would go if they weren’t forced to go another way. Cause its like laws…

Padgett

Isn’t this how we evolved?

Rice

Huh?

Padgett

That’s how we evolved—with tribes.

Padgett

Tribal democracy, that’s the concept—the basic Aryan concept.

Metzger

In other words, does the national borders of the United States mean anything anymore?

Rice

No, I think, I consider myself a nation within myself. I’m just moving around, you know.

Metzger

In other words, I see it as part of a growing underclass that doesn’t have to remain an underclass. But it has the spirit and the ideas of what, in many ways, carved out a lot of things in this country. But national borders, though, seem to me—because whatever your forefathers did in this country, doesn’t mean anything, no matter how many wars they fought, it doesn’t mean anything. Because the third world people just fall over the border, and they’re all—they’re citizens, they’re in, and they get every right anybody else. Why, why would anyone have allegiance to a system that doesn’t take care of its own?

Rice

I have no idea.

Metzger

We’re trying to figure that out.

Rice

I don’t consider myself an underclass because I feel like, I’m in line with what I am. And so everything else in my life runs from that.

Metzger

Is there a better term then, than underclass?

Rice

I’m not sure, maybe it’s just a class apart. Because I feel like I’ve transcended it all.

Metzger

I like that, a class apart. That does sound better than underclass!

Padgett

Sounds like our guest isn’t a conservative Republican.

Metzger

I don’t—I think he’s out of the playpen.

Padgett

Okay!

Metzger

Gotta go. Thanks for being with us, Boyd.

Rice

Okay.

Metzger

Very good, very good. /shakes hands with Rice / And thank you, ladies and gentlemen, and be back again. We’ll have another hot one here on Race and Reason.

[ending title card]

Race and Reason has been provided by:

White American Political Association

For more information write:

P.O. Box 65

Fallbrook, CA

92028

‘copyright’ Alexander Foxe 1986